As we’ve discovered from other posts we don’t so much see as perceive. Our eyes and brain don’t function like a camera; light falling on our retina is only the beginning of a much greater mental journey. What we think we see is constructed within our brains and subject to may factors from expectation, emotional state and personal experience to our culture and beyond (we’ll investigate the impact of some of these things in other posts).

We’ve been taking on board visual messages since the first simple creatures floating in the seas could distinguish between dark and light, blue and yellow light. We’ve had a few billion years of evolution to get pretty good at this seeing lark, and now, here we are as humans, adept at reading complex visual signs from facial expressions to highly abstract symbols like road signs and everything in between. We take these skills very much for granted but not only are we informed by our eyes we’re also tricked on a regular basis.

So why does that happen?

Consider for a moment having to process data as though it were fresh to you every single time, here’s my try (no prizes for guessing what I’m describing): What’s this object? I’m sure I’ve seen one before somewhere. It’s about the size of my fist and it’s sort of shaped like a stone, there’s no edges to it. It’s quite smooth and shiny like a stone too but not as heavy so it’s definitely not a stone . Now what colour is it – it’s not like the sky, it’s much more like grass. Can I eat it? Blah blah blah…..arrrrrrrrgh! We’d starve!

And just imagine the trouble you’d get in to if you were out on the savannah looking at a lion and trying to do that process – we’d never have made it this far as a species! Simply for our survival our brains have to work outside of our awareness and flag up to our conscious processing only what we need to deal with or are concentrating on. Interestingly we can even pay attention to something without even knowing it’s there as Po-Jang Hsieh (Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore and MIT) and his colleagues Jaron T. Colas and Nancy Kanwisher of MIT discuss in their research – see it here if you want to get side tracked.

As our visual system is developed to interpret a three-dimensional world, two-dimensional images can cause us all sorts of difficulties for our processing. Our experiences help us develop a map, a ready reference, and our brain busily looks for patterns that we’ve come across before and then fills in holes with a best guess. Take perspective used by artists – that is purely a bit of visual trickery. The trompe-l’œil creations of the street artist Julian Beever are great for seeing this at work http://www.julianbeever.net/waterfall.html and optical illusions can clearly show our short comings. There’s loads out there on the web – here’s a randomly selected link to a few: http://www.optillusions.com/

In 2D representations our brains are having to fill in a lot of gaps, images are only patches of light, shade and colour and experience is required to be able to interpret them. Has anyone seen the Father Ted episode where Ted is trying to explain to Dougal that the plastic cows are small but the real cows are far away? If you need a good laugh you can find it here.

Here’s a classic illusion, the Kanizsa triangle – you just can’t help but see a triangle in the foreground now can you!

Our vision is best adapted for looking for change in our environment, particularly rapid change such as movement. Anyone who has switched a TV on with the sound off and still found their attention wandering towards the screen will understand this phenomenon

(And I blame the same phenomenon for our kids insatiable appetite for moving images on computer screens!).

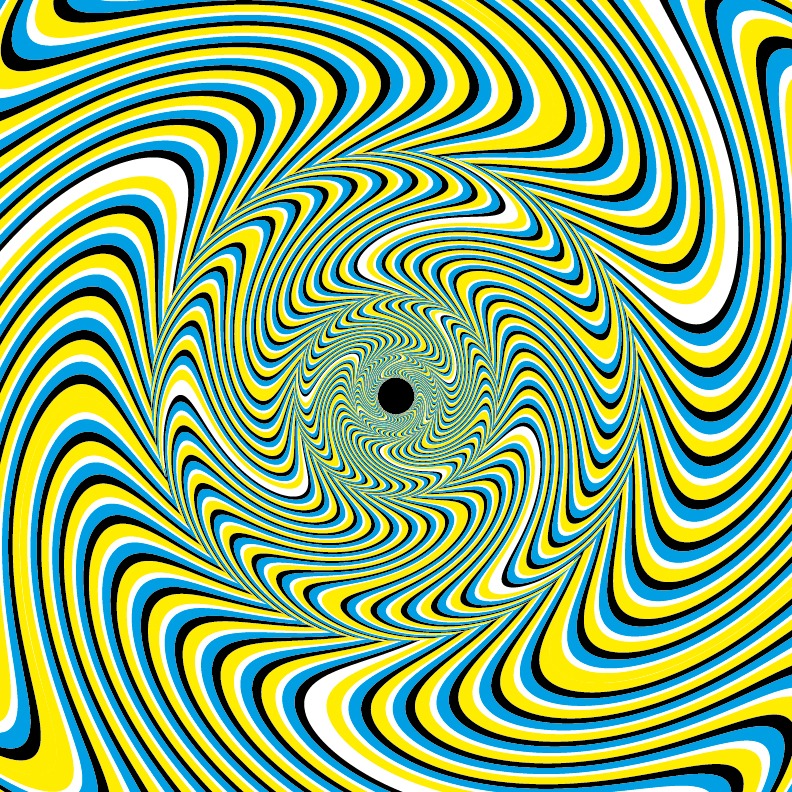

Take a look at this illusion – called a peripheral drift illusion, as the name suggests it’s particularly effective if you look at it off to one side so it’s in your peripheral vision. Differences in luminance and contrast seem to have an important role to play, as do tiny movements of the eye called “saccades” – if you want the scientific explanation you can click the link above. Apparently genetics also have their part to play in how strongly we can see this image some of us will see more movement than others.

I promise you this image isn’t animated!!!! Feeling sick yet? This one really gets to me! ©shutterstock

When it comes to seeing images we have come to believe what we see is real – this is because this belief is reinforced by experience: we see a cup we pick it up and drink – Q.E.D. therefore it is real. And it’s the assumption that what we see is real that get us into big, big trouble! You may think you’re simply seeing a politician talking on TV but there’s lots more going on in that image than we bring into our consciousness and think about… but that’s for next time…